Revisiting Mashal Khan’s family a year after his lynching

Nazar ul Islam

The young Pakistani student’s murder by a mob on a university campus was another “blasphemy killing,” one of the dozens since the 90s. A year on, his family struggles to reconcile with the tragedy.

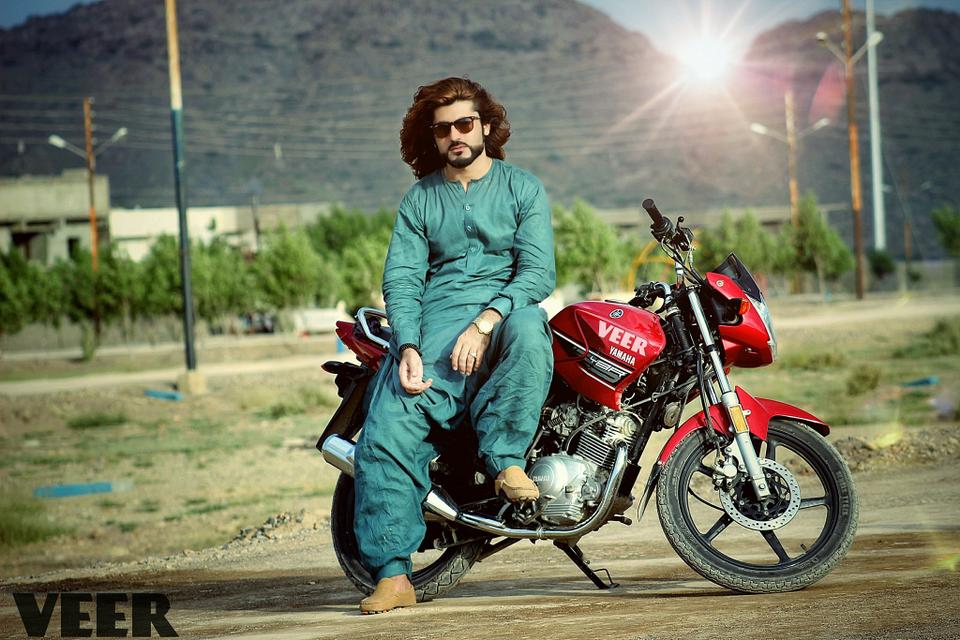

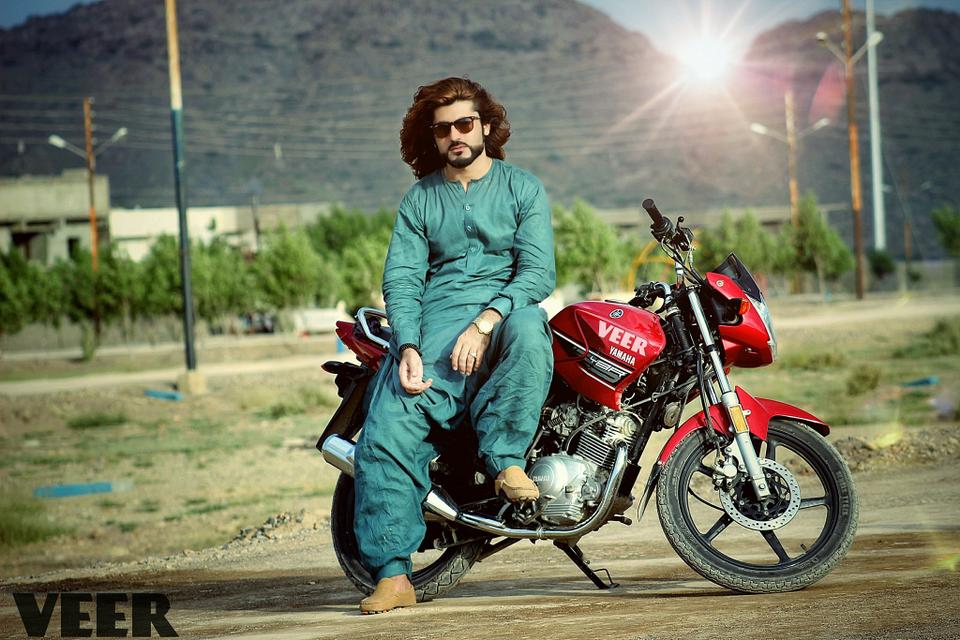

Mashal Khan was 23 when he was shot, stripped naked and beaten to death by a crowd at his university in Mardan, Pakistan. Mashal was a supporter of student rights and was known for criticising university policies which went against the good of the students. (Mashal Khan /Facebook)

Mashal Khan was 23 when he was shot, stripped naked and beaten to death by a crowd at his university in Mardan, Pakistan. Mashal was a supporter of student rights and was known for criticising university policies which went against the good of the students. (Mashal Khan /Facebook)

On March 26, Muhammad Iqbal brought home a white cake. He put some candles on it and asked his wife Syeda Bibi to join him. The cake read: Mashal Khan Shaheed. Mashal Khan, the martyr.

The date had always been a special occasion in their lives but this year was different. This year they were going to cut their son Mashal’s birthday cake for him, because on April 13, 2017, Mashal was lynched.

Surrounded by Mashal’s awards and trophies and photographs on white-washed walls, Iqbal handed the knife to Syeda Bibi and sat down, holding a picture of Mashal on his lap.

Syeda Bibi tried to blow out the candles but even six tries weren’t enough for her to find the energy within; Iqbal had to help her. She took the knife, sliced the white cake and put it aside without a taste.

April 13 marks one year since Mashal was falsely accused of posting blasphemous content online, an accusation so grave in Pakistan that it incited a crowd of students and clerical staff at Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan to beat the 23-year-old journalism student to death

“He was killed in broad daylight — at a place where people come to seek knowledge,” Iqbal said. “We spent last year going through great difficulties.”

Mashal was shot in the head and the chest at close range, stripped, his body battered and thrown from a second-floor window.

“It wasn’t just a simple murder,” his father told TRT World.

An investigation into the circumstances surrounding Mashal’s brutal death revealed blasphemy was used as a pretext by a student group affiliated with several political parties in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) where the university is based. The report and Mashal’s friends said it was his vocal criticism of the university’s administration and support for students rights which led to the plot against him.

Blasphemy relating to the Muslim faith is punishable by death according to Pakistani law and the mere suggestion that a person has committed blasphemy has resulted in the murders of dozens since the law was introduced.

The fear of mere association with someone who has been accused of blasphemy kept many of Mashal’s neighbours away from the funeral held in the family’s village. The local cleric initially refused to lead the funeral prayers.

Iqbal’s hands were weak at Mashal’s funeral, and his legs gave way, but he promised himself something as he lowered his son’s body into the grave.

“I know my Mashal isn’t coming back to the world. But I will fight to get [him] justice, so nothing like this can happen to another innocent child in this country,” a tearful Iqbal said.

And since then, Iqbal hasn’t stayed silent.

He travels from one corner of the country to the other — even abroad — to campaign for justice.

“Someone had to take this step for the future of our kids,” Iqbal said, referring to myriad threats students face in the region. Over 130 students and over a dozen others were slaughtered in an ambush by militants on the Army Public School in Peshawar in 2014.

Iqbal and Syeda Bibi’s family was never entirely safe after Mashal’s murder.

Aimal, their other son, works for the Pakistan Air Force.

Their two daughters couldn’t continue going to school or college because of security concerns. Although there haven’t been any direct threats, Iqbal is scared about their safety.

“There wasn’t any overt danger to Khan as well,” Iqbal said. “You don’t know about hidden threats, and society has become extremely polarised following the tragedy of my son,” he said.

The love for education was something the two sons and two daughters had in common. When one day the four children came home with five medals, Iqbal remembers the pride he and his wife felt, which one of his relatives tried to temper with a warning against nazar or envy of others.

Iqbal wanted Mashal to become an engineer and sent him to Moscow to study but his son had different dreams. Mashal wanted to become a journalist. He wanted to unearth the truth, and that desire is what Iqbal — and the investigation report — said cost him his life.

In February, an anti-terrorism court (ATC) sentenced one man to death and five others to life in prison for the lynching of Mashal. Initially, 26 defendants were acquitted and 25 were sentenced to prison time. Later a high court acquitted the 25 sentenced by the ATC.

The family and their lawyer don’t think the verdict reflected the gravity of the crime.

Fazal Khan is one of the lawyers on the Mashal case. Fazal’s 14-year-old son Omer was one of the children killed by the Pakistani Taliban in the Army Public School attack on December 16, 2014.

“Mashal’s death reminds me of my deceased son. They say those who lose their mothers always try and find love in other people’s mums,” Fazal said. “I think I am fighting for my son while I fight Mashal’s case.”

Although Fazal isn’t completely convinced by the court’s judgement, he is still optimistic. “I know there are weaknesses in the Pakistani judicial system, but that doesn’t mean we should lose hope in getting justice. We have to continue our struggle within the existing system,” Fazal said.

“There is no doubt that the nature of Mashal’s death is different from my son’s, but I will keep fighting for each child of this nation.”

Iqbal sees some victory in his own struggle for the children of Pakistan.

He pointed to the recent protests organised by young Pashtuns — the major ethnic group from northern Pakistan — after one of their own was killed by the police in Karachi in a “fake encounter.”

Senior Karachi police official Rao Anwar led a police operation against “Taliban militants” and killed Naqeebullah Mehsud, a young aspiring model from South Waziristan, in a staged shoot-out.

Naqeebullah Mehsud was taken into custody by the police after which he was killed in a staged encounter by police led by Rao Anwar, a famous senior Karachi police official, in January 2018. (Naqib Maseed/Facebook)

Naqeebullah Mehsud was taken into custody by the police after which he was killed in a staged encounter by police led by Rao Anwar, a famous senior Karachi police official, in January 2018. (Naqib Maseed/Facebook)

The Pashtun Tahafuz Movement — a left of centre movement for the protection of Pashtun rights — has mobilised thousands in a series of protests against extrajudicial arrests, killings and disappearances.

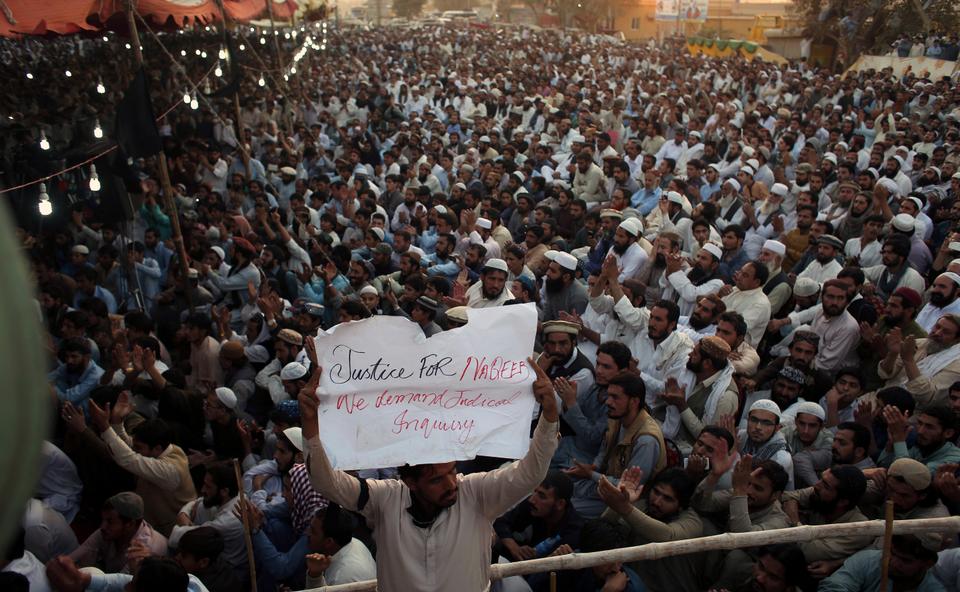

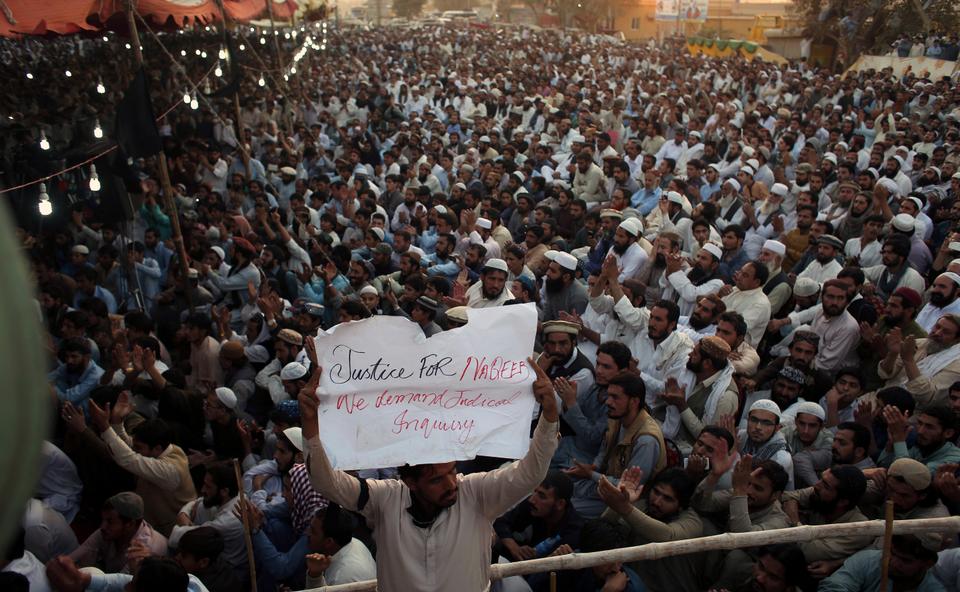

People rally to condemn the killing of 27-year-old Naqeeb Ullah Mehsud, in Karachi, Pakistan, on January 25, 2018. Thousands of Pakistanis, led by the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement, are rallying in major cities to demand the arrest of a police commander charged with killing the aspiring model. (Shakil Adil/AP)

People rally to condemn the killing of 27-year-old Naqeeb Ullah Mehsud, in Karachi, Pakistan, on January 25, 2018. Thousands of Pakistanis, led by the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement, are rallying in major cities to demand the arrest of a police commander charged with killing the aspiring model. (Shakil Adil/AP)

As for Iqbal, he is still trying hard to keep his son’s case alive. This can be hard in an environment where those who are suspected to have had a hand in killing Mashal have been set free amid celebrations by religious parties in Pakistan.

Although Mashal was posthumously exonerated, the father of one of the students accused of being involved in Mashal’s murder, told the BBC that Mashal committed blasphemy. “He was responsible for his own killing.”

Having lost his son, Iqbal wants to see the youth of Pakistan happy.

Last month the Pakistan Super League cricket final was held in Karachi and thousands of supporters cheered the players inside the Karachi stadium.

“They enjoyed the cricket match and we were happy seeing them happy there.” But, he added, “wouldn’t it be good if Peshawar and other parts of Pakistan affected by terrorism could also host such activities?”

“In my opinion they (Pashtun) are the people who need some happiness and that’s the way towards their success,” said Iqbal.

Speaking to TRT World just before April 13, Iqbal and Syeda Bibi’s family struggled with the first anniversary of their son’s death.

Iqbal recalled Mashal last visited his family home in February 2017, when his niece was born. “He hugged the newborn baby girl, kissed her and gave her some presents before he left for university.”

Iqbal said that, soon after their son left, Syeda Bibi called Mashal, asking him to come back soon as she was missing him terribly.

“Mashal replied. ‘Mum. don’t worry. I am all right. I have exams at the moment. But I promise I will come on Thursday.”

Mashal did come home on that same Thursday, but in a blood-soaked shroud.

Mashal Khan was 23 when he was shot, stripped naked and beaten to death by a crowd at his university in Mardan, Pakistan. Mashal was a supporter of student rights and was known for criticising university policies which went against the good of the students. (Mashal Khan /Facebook)

Mashal Khan was 23 when he was shot, stripped naked and beaten to death by a crowd at his university in Mardan, Pakistan. Mashal was a supporter of student rights and was known for criticising university policies which went against the good of the students. (Mashal Khan /Facebook) Naqeebullah Mehsud was taken into custody by the police after which he was killed in a staged encounter by police led by Rao Anwar, a famous senior Karachi police official, in January 2018. (Naqib Maseed/Facebook)

Naqeebullah Mehsud was taken into custody by the police after which he was killed in a staged encounter by police led by Rao Anwar, a famous senior Karachi police official, in January 2018. (Naqib Maseed/Facebook) People rally to condemn the killing of 27-year-old Naqeeb Ullah Mehsud, in Karachi, Pakistan, on January 25, 2018. Thousands of Pakistanis, led by the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement, are rallying in major cities to demand the arrest of a police commander charged with killing the aspiring model. (Shakil Adil/AP)

People rally to condemn the killing of 27-year-old Naqeeb Ullah Mehsud, in Karachi, Pakistan, on January 25, 2018. Thousands of Pakistanis, led by the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement, are rallying in major cities to demand the arrest of a police commander charged with killing the aspiring model. (Shakil Adil/AP)