Can Venezuela Be Saved?

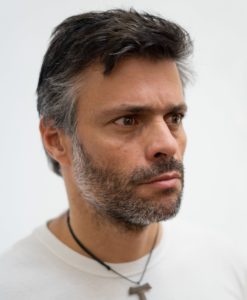

As a nation unwinds, Leopoldo López, the opposition’s most prominent leader, sits under house arrest and contemplates what might still be possible.

Since the publication of this article, armed guards from the Venezuelan intelligence service have raided and occupied the residence of Leopoldo López. Members of the Venezuelan National Assembly gathered in front of the house, along with local media and citizens, to protest the invasion and threats by the Venezuelan government that López will be returned to military prison.

There’s a page in a book in a stack on the floor at the house of Leopoldo López that I think about sometimes. It’s a page that López revisits often; one to which he has returned so many times these past few years, scribbling new ideas in the margin and underlining words and phrases in three different colors of ink and pencil, that studying it today can give you the impression of counting the tree rings in his political life.

The book is not set out in a way to invite this kind of attention. Almost nobody is allowed to enter the López house, for one thing, being surrounded all day and night by the Venezuelan secret police; but also, for all his flaws and shortcomings, López just isn’t the sort to dress up his library for show. Pretty much every book in the house is piled up in a stack like this one — row upon row of stacked-up books rising six to eight feet from the dark wood floors, these gangly towers of dog-eared tomes, some of them teetering so precariously that when you see one of the López children run past, you might involuntarily flinch.

The particular book I have in mind is a collection of political essays and speeches. It was compiled by the Mexican politician Liébano Sáenz, with entries on the Mayan prince Nakuk Pech and the French activist Olympe de Gouges. The chapter that means the most to López begins on Page 211, under the header “Carta a los Clérigos de Alabama.” This is a mixed-up version of the title you know as “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” which was written by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963. King was in Birmingham to lead nonviolent protests of the sort that everybody praises now, but it’s helpful to remember that in 1963, he was catching hell from every quarter. It wasn’t just the slithering goons of the F.B.I. wiretapping his home and office or the ascendant black-nationalist movement rolling its eyes at his peaceful piety, but a caucus of his own would-be allies who were happy to talk about civil rights just as long as it didn’t cause any ruckus. A handful of clergymen in Birmingham had recently issued a statement disparaging King as an outside agitator whose marches and civil disobedience were “technically peaceful” but still broke the law and were likely “to incite to hatred and violence.”

On the page in the book at the López house, King fires back. Writing from a cramped cell without a mattress or electric light, he scrawled a response on scraps of paper for his cellmate to smuggle out. Near the top of the page, López has underlined a passage in pencil where King condemns the complacency of “the white moderate” and the suggestion that peaceful protesters are responsible for the violent response of others. “We who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension,” he writes in a passage López marked with green: “We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive.” King then compares civil disobedience to the lancing of a boil, before culminating in a passage that López has flagged at least half a dozen times — with some words underlined in red, others highlighted pink, a handful of phrases boxed in green and three large arrows drawn into the margin beside the words: “Injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates.”

At a certain level, it’s unremarkable when a politician studies King, and among the people López tries to emulate, I wouldn’t put King at the top. He is more directly influenced by the former Venezuelan president Rómulo Betancourt or, for that matter, by his own grandfather Eduardo Mendoza, who was Betancourt’s adviser. But when you consider the path that López has followed these past few years in prison, the choices he’s made, the compromises and blunders, the price he has paid to speak his mind and the price now of his silence, if you want to understand the impact of four years in captivity and nine months in solitary confinement, the message from King in Birmingham is a very good place to start.

López was arrested in February 2014 after leading a public protest that turned violent. Prosecutors acknowledged in court that López was technically peaceful, but they accused him of inciting others to hatred and violence. Before his arrest, he was among the most prominent and popular opposition leaders in Venezuela. Polling suggested that he could defeat President Nicolás Maduro, the unpopular successor to Hugo Chávez, in a free election. At trial, he was sentenced to 13 years and nine months in prison. Since then, he has become the most prominent political prisoner in Latin America, if not the world. His case has been championed by just about every human rights organization on earth, and he is represented by the attorney Jared Genser, who is known as “the extractor” for his work with political prisoners like Liu Xiaobo, Mohamed Nasheed and Aung San Suu Kyi. The list of world leaders who have called on the Venezuelan government to release López includes Angela Merkel of Germany, Emmanuel Macron of France, Theresa May of Britain and Justin Trudeau of Canada; it is that rarest of political causes on which Barack Obama and Donald Trump are in agreement. In Venezuela, López has become a kind of symbol. His name and face are emblazoned on billboards, T-shirts and banners — but there’s widespread disagreement on precisely what he represents. The Venezuelan government routinely disparages him as a right-wing reactionary from the ruling class who wants to reverse the social progress of chavismo and restore the landed aristocracy; the Venezuelan right, meanwhile, considers López a neo-Marxist, whose proposal to distribute the country’s oil wealth among the people would only deepen the chavista agenda.

For three and a half years in prison, López refused to let anyone speak for him. Though he was prohibited from granting interviews or issuing public statements and was often denied access to books, paper, pens and pencils, he managed to scribble messages on scraps of paper for his family to smuggle out, and he recorded a handful of covert audio and video messages denouncing the Maduro government. From time to time, he could even be heard screaming political slogans through the bars of the concrete tower in the military prison where he was kept in isolation.

López was released to house arrest last July on the condition that he fall silent. He promptly climbed the fence behind his house to rally a gathering crowd, then issued a video message asking his followers to resist the government. Three weeks later, he was back in prison; after four days, he was released again. Ever since, to the great bewilderment of his supporters, he has vanished from public view. While the country descends into an unprecedented crisis — with the world’s highest rate of inflation, extreme shortages of food and medicine, constant electrical blackouts, thousands of children dying of malnutrition, rampant crime in every province, looting and rioting in the streets — López has said nothing.

Venezuelan families forced to leave their homes because of economic conditions now live in Colombia under a bridge that connects to Venezuela. Credit Sebastián Liste/NOOR, for The New York Times

Today his critics include not just the hard-line left and right but much of the Venezuelan majority that once saw him as a future president. They don’t understand what López is doing inside that house, tucked away on that leafy street in the wealthy suburbs of Caracas, but they suspect that he has grown comfortable there, reunited with his wife and children; that his family’s wealth insulates him from the economic crisis; that the secret police who surround his home protect him from rising crime; and they can’t help wondering if Leopoldo López has finally given up. They know, as he knows, that if he issued a public statement or released another video message, if he climbed the fence behind his house to address his followers again, the secret police would swoop in to haul him back to prison. But López never let the risk of prison stop him before. He would have at least one chance to speak, and they wonder why he hasn’t.

There’s a flicker onscreen whenever López connects, then a blur of pixelated color as his face comes into view. On different days, at different times, he can look very different. There are mornings when he turns up in an old sweatshirt with unkempt hair and a weary smile, and others when he appears in a pressed oxford shirt with parted hair and black-rimmed glasses that do nothing whatsoever to obscure the haunted air of a sleepless night.

I think of a Saturday in October. It was a few minutes after noon. I was out for a walk with my kids when a message from López popped on my phone. “The situation is very delicate,” he wrote. “I may be on the borderline of going back to prison.” Scrambling home, I opened my laptop and after a minute, he appeared onscreen. López is 46, 5-foot-10 and fit. He was sitting at the desk in his living room with his hair poking off at angles, and the cast of his expression was an admixture of fear, fatigue and fury.

When the audio clicked on, I asked what was happening. López took a deep breath. He propped an elbow on the desk and rested his head in his hand. “Last night around 7:30, they came to my house — more than 30 officers of the political police,” he said. “They had more than 10 cars. They closed the entire street. And then they came into my house.” For more than a decade, López has employed a private security detail, as political opponents stormed his events with masks and guns, sprayed his car with bullets and murdered one of his bodyguards. Under house arrest, he is allowed to maintain a small guard outside. During the raid, López said, the police took his chief of security into custody, and no one had heard from him since. “There was absolutely no reason, legally, they could take him, and they have not allowed any lawyers to go in to see him,” López said. He looked down at his desk and shook his head. “So that’s the situation,” he said quietly. “And I wanted to tell you that I’m willing to go forward with this, what we’re doing.”

At that point, we had a very different sense of what we might be doing. We had been in contact for only a few weeks. I first reached out to López through an intermediary in August, not long after his return to house arrest, and by September we were talking a couple of times a week, usually for a couple of hours at a time. This was a clear violation of his release. An order from the Venezuelan Supreme Court specifically forbid him to speak with the news media, and we didn’t expect to get away with it. At a minimum, it was safe to assume that his house was bugged for sound, but there were probably hidden cameras as well, and his computer was surely hacked and his internet activity monitored.

The world is full of byzantine methods to communicate through encrypted channels, but most of them are obviated for a person who is trapped in a digital glass house and surrounded by the state security of an authoritarian regime. We did what little we could to be discreet, knowing it wasn’t much. Rather than connect on Skype or FaceTime, we used an obscure video service, which seemed at least marginally less likely to be a platform the police had practice hacking. Whenever we spoke, López wore a pair of headphones, so a conventional audio bug would only pick up his side of the conversation, and we adopted the general posture of old friends catching up. This was not as much of a stretch as it may seem. López is three years older than I am and a graduate of Kenyon College, where we briefly overlapped but never met. From time to time, one of us would mention the school or someone we both knew there, and our kids would periodically wander onscreen to wave hello.

All of this seemed hopelessly primitive in the face of state surveillance, but then again, it seemed as if it might be working. Once in a while a big white van would appear in front of his house and the connection would go dark, but within an hour or two, the van would leave and we’d get back online. Neither of us could explain why, if government agents were listening, they hadn’t shut us down or come inside to arrest him. There was every reason to believe that they would. In our conversation that day in October, López mentioned that the agents raiding his home had given just one reason: They believed he was talking to a reporter and recording a video message. This led to a curious moment in our conversation, as the recording system on my end of the interview captured his denial. “It’s not true,” he said to anyone listening. “I’ve had no contact with any journalist!”

I don’t mean to make light of the situation, but the truth is, we often did. Venezuela was coming off a summer that promised change. In July, the opposition movement sponsored a nonbinding referendum on the government’s plan to rewrite the Constitution. With more than seven million ballots cast, 98 percent of voters opposed the government. Soon after that, emissaries from the government approached opposition leaders to begin a formal negotiation, with a primary focus on the release of political prisoners. Even as we spoke that day in October, the country was preparing for regional elections in which opposition candidates were expected to win by a landslide.

There were contradictory signals, of course, but the trajectory was toward transition. This was a time when headlines everywhere predicted a “turning point” for Venezuela, and I think on some unspoken level, López was counting on it. It was a gamble to speak publicly, but it wasn’t crazy to imagine that by the time this article appeared, the political landscape could be transformed — that the opposition, which already held a supermajority in Congress, could win a similar proportion of governorships; that a regional victory would carry into the municipal campaign in December; that they would enter this year’s presidential race with momentum against a deeply unpopular president, polling at 25 percent; that the negotiation for political prisoners might even allow López to challenge Maduro himself. Polls at one point suggested he could win the presidency by a margin of 30 percent.

This was the conversation that I think we expected to have last summer: a look at the next chapter for Venezuela and the role he might play. Instead, with each passing day, the possibilities grew more slender. When voting began on the morning after that October call, nothing went as expected. The polling places for more than 700,000 citizens had mysteriously moved, in some cases so far that it would take hours for them to travel on crowded buses. Even so, by evening, officials were reporting overwhelming turnout and a breathtaking upset: Candidates from the ruling party had swept all but five of the governor’s races. Amid a global outcry of fraud, several opposition parties withdrew from the municipal elections — and the government responded by invalidating those parties. The scheduled negotiation with opposition leaders began in November. In January, the talks collapsed. In February, officials dissolved the whole coalition of opposition parties.

Political leaders of every stripe were being detained by the secret police. The second-ranking member of Congress went into hiding at the Chilean Embassy, and about a dozen mayors fled the country. The state, the economy and the social fabric were unraveling all at once. Everywhere, people were leaving Venezuela any way they could. They piled into ramshackle boats and died at sea. They walked the highway toward Brazil, collapsing in heat and sun. They poured into Colombia, tens of thousands each day, a refugee crisis comparable in number to the flight of the Rohingya to Bangladesh. It seemed that every time I spoke with López, another friend had taken sanctuary in an embassy, gone to prison or fled.

Venezuelans crossing into Colombia in February. Credit Sebastián Liste/NOOR, for The New York Times

I asked him one day recently how he was managing the pressure. The secret police had just returned to his house with another order to arrest him, and he was saying goodbye to his wife, Lilian, who was eight months pregnant, when one of the agents received a phone call to suspend the arrest. It wasn’t clear when they might return.

“How are you feeling?” I asked.

“It’s tough,” he said. “It’s tough after what happened. Every day I think is the last day I have to be with my kids.”

I asked if he ever thought about trying to escape. “Most people tell me that I should,” he said. “But I believe a commitment to the cause means that I need to take the risk.” As he spoke, I realized that what we had actually been talking about all these months, what he had been trying to communicate through this portal from his silence, was never really about the future of Venezuela or the role he hoped to play, and it wasn’t about political ambition or the next chapter in history. It was something fundamental that kept coming up in offhand remarks. It was something that he learned in prison about the history we’re always in.

The line of people waiting to leave Venezuela begins to form an hour before dawn. Migrants drift through unlit streets in the border town of San Antonio to gather at the foot of the Simon Bolívar Bridge, where they wait beneath a huge red banner that reads, “Don’t speak ill of Chávez.” When the checkpoint opens at 6 a.m., they push forward, moving shoulder to shoulder down the two-lane highway into Colombia. There will be no tapering off through the day; there is no end to the people coming. Some have traveled more than a week to get here. It only takes a glance to see what sort of people they are: every sort, of every age, from every profession and social stratum — young families and older couples and clusters of itinerant boys and solitary young women looking several weeks overdue. If you stop for a moment on your way across the bridge, you can almost feel the deflating wind of the Venezuelan exodus at your back.

Historians have come up with all sorts of arguments about the arc of Venezuelan history and how things went so wrong. A couple of points strike me as indispensable to any case: Venezuela is the birthplace of Latin American independence and sits on the largest proven reserves of oil in the world. How you interpret the role of these factors in any given historic event is a matter of personal politics and granular debate, but you can’t have a serious discussion about Venezuela without taking both into account. For most of the past century, the country has whipsawed between political movements that court and reflect and sometimes renounce the legacy of anti-imperialism and the towering glut of riches.

Like most of its neighbors, Venezuela endured a succession of caudillo strongmen in the early 20th century and responded with a radical leftist movement in the 1950s and ’60s. Unlike its counterparts in neighboring countries, the Venezuelan left didn’t get very far. Some of them took up arms in the mountains and limped through a series of gunfights, but by the end of the ’60s, most had returned to a marginal place in conventional politics. One of the few who stayed in the fight was a guerrilla named Douglas Bravo, who called his nationalist political ideology “Bolívarianism.” Bravo finally settled in Caracas in the 1980s, where he developed inroads with disaffected citizens and soldiers in the Venezuelan Army. Two of the acolytes he courted were the brothers Adán and Hugo Chávez, who welcomed the idea of leading a Bolívarian coup.

It took about a decade of recruitment and planning, during which time the Venezuelan establishment seemed to be doing everything possible to help them. For decades, the two major parties essentially passed the presidency back and forth in a power-sharing agreement that gave little heed to the country’s swollen underclass. Venezuela’s economic fault lines had become so fraught that in 1989 a rise in bus fares helped trigger deadly riots. By the time the Chávez brothers were ready to attempt their coup in 1992, a lot of Venezuelans were just happy to see the establishment take a hit. Although the coup failed and Chávez spent two years in prison, he emerged as a minor celebrity. By 1998, he was running for president.

Gas smugglers from Venezuela on one of the dozens of rural routes that connect Venezuela and Colombia by crossing the Táchira River. Credit Sebastián Liste/NOOR, for The New York Times

It’s easy now, with the country in turmoil, to dismiss the whole project of chavismo. But the election of Chávez in 1998 coincided with a groundswell of social and political movements for whom Chávez, with his energy and outrage, pledging to crack down on corruption and raise the minimum wage, seemed a natural ally. Whatever else Chávez became, he delivered on many of his promises. During his tenure, unemployment fell by half, the gross domestic product more than doubled, infant mortality dropped by almost a third and the poverty rate was nearly halved. You can chalk this up to other factors, like a tenfold increase in the price of oil that showered his administration with revenue, and you can argue that Chávez failed miserably to anticipate the next downturn in oil prices, but you can’t really accuse him of making promises to the poor and then delivering to the rich, or keeping all the money for himself. Under his watch, income inequality dropped to one of the lowest levels in the Western Hemisphere. Chávez didn’t have to steal elections. He was wildly popular among the poor and put his proposals up for election almost every year. He introduced touch-screen voting, with thumbprint recognition and a printed receipt, an electoral system that Jimmy Carter described as being, among all the countries he had monitored, “the best in the world.”

Chávez also possessed an autocratic impulse that was jarring from the start. Over the course of 14 years in office, he dismantled the country’s democratic institutions one by one. There’s an interesting debate among political theorists about what to call a leader who destroys a democracy with democratic support. It’s possible to think of Chávez as a totalitarian or a tyrant for suppressing his opponents while rejecting the term “dictator” to describe a popular president. Chávez made no secret of his contempt for the country’s extant political system; he couldn’t even get through his first inauguration without ad-libbing, in the middle of the swearing-in ceremony, a promise to rewrite the Constitution — which he promptly did, consolidating power over the Legislature and the courts.

Any limit that Chávez might have been willing to accept on his power vanished in April 2002, when a junta of military officers and right-wing leaders tried to oust him in a coup. For about 36 hours, they installed as president a man named Pedro Carmona, who was the director of Venezuela’s primary business consortium. Carmona’s government proceeded to undermine institutions at a clip that would make even Chávez blush. In the single day of his presidency, he dissolved the Legislature, the Supreme Court and the Constitution and began to cleanse the Venezuelan military of anyone loyal to Chávez. This was too much even for critics of chavismo. The streets of Caracas exploded in protest, and crowds descended on the presidential palace. Soon Chávez was back in office, consolidating power more quickly than ever. He persecuted rivals and stacked the courts and levied so many restrictions on industry that the private sector essentially disappeared.

You can think of the decade between the coup and his death in 2013 as a gradual process of bleeding out public resources for public consumption. At a basic level, Chávez just wasn’t very good at managing an economy. His budget spent the revenue from skyrocketing oil prices, and his control of the state oil company proved disastrous. Chávez believed that because oil reserves are a finite resource, it made sense to limit production and drive up the price of every barrel. This way of thinking is widely disputed, if not debunked. Producers are constantly developing new ways to find and access oil; between the American shale revolution and rising competition from alternative energy, most oil companies today want to pump as much oil as quickly as they can.

When Chávez took power in Venezuela, the state oil company was producing about 3.4 million barrels per day. Its leadership planned to almost double the volume. Instead, through a combination of Chávez’s misguided theories and a general failure to invest in the company and installing his personal henchmen to run it, production of Venezuelan oil has fallen by nearly half. Oil prices have also dropped considerably over the past few years, but the country has little else to sell. According to the most recent data, oil accounts for about 95 percent of Venezuelan export earnings. Much of that oil is being shipped to Russia and China in exchange for help with the national debt, giving both countries expansive claims on Venezuelan production. The more desperate the Maduro regime becomes, the more these countries stand to gain.

What you’ve got then is a domino cascade: less and less oil, at lower and lower prices, with nothing else to sell, and a dependence on foreign money at the expense of future income. The final chip in the cascade has been Venezuela’s currency. As national revenue plunged, leaving a gap in the annual budget, Chávez and Maduro turned to the central bank to print more money. The number of Venezuelan bolívars has grown exponentially in recent years. When Maduro took power in 2013, the country’s monetary base was about 250 billion bolívars. Today, it’s more than 60 trillion. For a sense of scale, imagine if you had $5,000 yesterday, and today it was $1.2 million. I don’t mean to suggest any meaningful comparison between your savings account and a national economy, but it’s not difficult to imagine how a huge increase in money distorts the way people spend it.

Most countries around the world produce official inflation reports. The Venezuelan government has essentially stopped. One of the world’s leading experts on hyperinflation is a professor at Johns Hopkins University named Steve Hanke, who has advised governments around the world on runaway inflation, including Venezuela in 1995 and ’96. Hanke has been tracking the Venezuelan economy closely for the past five years, producing a daily estimate of the country’s annual inflation. As I write this, his most recent estimate was 5,220 percent. The International Monetary Fund has predicted that inflation in Venezuela will reach 13,000 percent this year.

A Venezuelan gas smuggler. Credit Sebastián Liste/NOOR, for The New York Times

Joint operations between the police and the Colombian military try to stop smuggling. Credit Sebastián Liste/NOOR, for The New York Times

This is what you see in the faces of the people on the bridge leaving Venezuela. You see people trying to escape a country where basic supplies are nearly impossible to find and prohibitively expensive, where the price you paid for a car a few years ago won’t buy a loaf of bread today. You see families with roll-aboard luggage and no plans to go back, and children who are crossing just for the day with nothing but a bunch of bananas. They will sell the bananas for a pittance in Colombian pesos, then return home to convert the cash into a small fortune of Venezuelan currency — at least for a few days, when their money will be worthless again.

López was born to privilege in the wealthy enclaves of northeastern Caracas. His father, Leopoldo López Gil, was the head of an international scholarship program who sat on the editorial board of a center-left newspaper. His mother, Antonieta Mendoza, was a distant relative of the first president of Venezuela, Cristóbal Mendoza, and of Simon Bolívar. Each side of the family had long traditions of political activism and dissent. López grew up hearing about his great-grandfather’s 17 years in prison and his grandfather’s role in the underground resistance. “We always heard those stories,” his sister Diana told me. “I think it was always in Leo’s memory.” López said he relished the history in part because it felt so alien, snapshots of a country that he couldn’t quite imagine. “I saw it as a faraway past of black-and-white pictures,” he told me. “I never thought that in the 21st century, my own reality could be similar.”

The Venezuela that López inhabited was the wealthiest country in Latin America. It welcomed tens of thousands of immigrants every year and had been a democracy since 1958. Skateboarding, swimming, crazy for girls, López at 13 was largely removed from the country’s systemic inequities. He was on a school trip to the rural state of Zulia, passing through the region’s oil fields, when he found himself unexpectedly moved by the destitution around him. “I was shocked by the poverty level,” he recalled, “and the fact that below these very humble barrios and dramatic poverty, we had huge potential.” Diana told me that López began making trips into western Caracas “to try to understand the dynamics of the city.” At school, he immersed himself in student leadership, becoming vice president of the student government and captain of the swimming team.

After college, López briefly enrolled at Harvard Divinity School but left after one semester to enroll in the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. He completed a master’s thesis on the legal and economic framework of oil production in Venezuela and traveled through Nicaragua and Bolivia to study the impact of microloans. In 1996, he returned home for a job in the strategic planning office of the state oil company.

Watching the ascent of Chávez in 1998, López was unimpressed. “Ever since the establishment of the Venezuelan republic in 1830, for the most part we’ve had military in the government,” he told me. “And that has created a militaristic way of governing.” I asked López if there was ever a point when he reconsidered his opinion of Chávez. “For one day,” he said with a laugh. “When he spoke about microcredits to the poor.”

As Chávez took office and began making plans to rewrite the Constitution, López campaigned for a seat in the constitutional convention. He lost that election but rallied with two other failed candidates to create a new political party, then he entered the 2000 campaign for mayor of the city’s most affluent borough. He won with 51 percent of the vote.

Over the next eight years, López gained international attention as mayor of Chacao. He began by raising business taxes while offering incentives for companies to move into the district. With revenue up, he commenced a series of public works, building health clinics and schools, a theater, a public market and a recreation center. Still unmarried and in his early 30s, he was comically hands on, forever rolling up his sleeves at groundbreaking ceremonies and appearing, in Cory Booker fashion, at predawn crime scenes to consult with detectives in the blinking red light. In a city notorious for crime, he implemented policing measures that were popular in the United States — think “zero tolerance” and “broken windows” and “compstat” multivariate analysis. His platform, then, was a heterodox mash-up of initiatives that span the political spectrum, from lefty measures like raising corporate taxes to conservative models of policing. Residents loved it. In 2004, he was re-elected with 81 percent of the vote, and during his second term he met and married a prominent television personality named Lilian Tintori. In 2008, López left office with 92 percent approval and a ranking from the City Mayors Foundation as the third-best mayor in the world.

Skimming this résumé, you can see why people often regard López in a gauzy half-light, but even as he thrived as mayor of Chacao, he was becoming a polarizing figure. By the end of his second term, he was one of the most promising young politicians in Venezuela and one of the least capable of getting along with others. Within the opposition movement, López represented a radical wing. The word “radical” is often used about López in a misleading way. He favors a mixed economic model of expansive social services in health care, education and housing, offset by a large private sector of manufacturing and industry. On the spectrum of American politics, he would probably land in the progressive wing of the Democratic Party.

Where you can describe López as a radical is the way he approaches political activity. He believes that a relentless campaign of street demonstrations and civil disobedience is essential to challenge an authoritarian government. On any given day in 2002, a person walking through Caracas had a good chance of spotting the mayor of Chacao standing on a bench in some public park, bellowing at a crowd through a megaphone. How useful this was to the project of building a mature political party with governing potential was a matter of opinion, but López believed that the movement would get nowhere by relying on decorous party mechanics.

One way to measure the success of a strategy is to study its response. López became a frequent target of physical and administrative attacks. From 2002 to 2006, there were three major attempts on his life, one of which left him cradling a bodyguard dying of a gunshot meant for López. During his tenure as mayor, he was accused by the comptroller’s office of paying municipal expenses from the wrong part of his budget and barred from seeking public office until 2014. López appealed the decision and prepared to run for mayor of Caracas. He was leading with 65 percent of the vote when the Supreme Court upheld the comptroller’s decision. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled the ban illegal and ordered Venezuela to let López run, but the government ignored the order and López has been forbidden to hold public office ever since.

By 2008, he was also clashing with other opposition leaders. He left the party he helped found, joined another and soon had issues with its leadership as well. In August, that party expelled him, and he began making plans to create yet another. American diplomats in Caracas weren’t sure what to make of López. A classified cable to Washington described his “much-publicized rebelliousness,” noting that López “will not hesitate to break with his opposition colleagues to get his way.” Another referred to him as “a divisive figure” who was “often described as arrogant, vindictive and power-hungry.”

Venezuelan migrants in Cúcuta. Credit Sebastián Liste/NOOR, for The New York Times

In 2012, still barred from running for office, López threw his support behind an opposition candidate in the presidential election. Chávez beat that candidate by a 10-point margin but died soon after, opening the door for a repeat campaign against Maduro. When the electoral board announced that Maduro had won by a single percentage point, López suspected fraud. He pushed for the opposition movement to stage a public demonstration. Most of the other opposition leaders dismissed the idea, but in January 2014, López called for his supporters to take the streets.

By February, protests were springing up in every province. On Feb. 12, López rallied thousands of students at the edge of a park in Caracas. After his speech, they marched to the office of the attorney general a mile away. Some of the protesters began throwing rocks at the building. Security officers emerged, and two protesters were shot. Though López was gone before the violence began, officials accused him of being the “intellectual author” of the skirmish, and the attorney general issued a warrant for his arrest.

López and Tintori took refuge that night in a friend’s apartment. They recorded a video message for the public. “I want to say to all Venezuelans that I do not repent,” López said. He spent a few days in hiding, then recorded another video asking his supporters to gather at a downtown plaza on Feb. 18, dressed in white as a sign of peace, to bear witness as he turned himself in.

That morning, he climbed on a motorcycle and rode into the city. A large crowd was gathering, and the police had set up checkpoints to intercept him. López tried to find a way around the checkpoints but couldn’t. He finally rode up to a cluster of police officers from the Chacao district and removed his helmet. The officers recognized him, saluted and waved him through. López saw the crowd extending in every direction. Thousands upon thousands of people had come dressed in white. He waded through them to a statue of the Cuban independence hero José Martí and climbed the pedestal to look over the sea of faces. Someone handed him a megaphone, and he raised it. “If my imprisonment helps to awaken a people,” he called out, “then it will be worth the infamous imprisonment imposed on me.”

After a short speech, he climbed down from the pedestal, where soldiers were waiting to arrest him. They pulled him inside an armored vehicle, but the crowd pressed in, rocking it. Minutes passed, then half an hour. The truck was trapped by the crowd. Someone gave López a handset connected to the vehicle’s outside speakers. He called to the crowd that he was safe and that they should clear a way for the truck to get through. Slowly, almost grudgingly, they parted the path for López to prison.

An opposition demonstration in Caracas in February. Credit Carlos Becerra for The New York Times

Officials placed López in a concrete tower on a military base outside the city, charging him with terrorism, arson and homicide. Amnesty International condemned his prosecution as “an affront to justice” and “a politically motivated attempt to silence dissent.” For his initial arraignment, he was taken from his cell in the middle of the night and marched outside to face a judge on a bus. The rest of the proceedings took place at the Palace of Justice in Caracas, a five-story edifice that sprawls across 1.5 million square feet downtown. Over the next 19 months, he traveled there nearly 100 times, in a motorcade of armored S.U.V.s, wearing a bulletproof vest, with his hands shackled together, wedged between two guards armed with machine guns and two more behind him. Each time López appeared in court, the Palace of Justice shut down.

The trial hinged on speech. No one accused López of being violent himself. Prosecutors scaled back the charges, arguing that he inspired violence in others. They brought in a linguistic expert to examine transcripts of his speeches and claimed that his message of peaceful protest disguised a “subliminal” call to violence. They introduced more than 100 witnesses, some of whom testified that they had received the subliminal messages. López tried to introduce his own witnesses, but the judge wouldn’t allow it.

A few words about the judge who signed his arrest warrant and a lead prosecutor and attorney general: They all repent. The judge who signed the warrant later admitted that she had been forced to do so. The lead prosecutor, after fleeing the country, denounced the case against López as “a farce,” saying “100 percent of the investigation was invented.” The attorney general, Luisa Ortega, escaped to Colombia last summer and says that the vice president of Maduro’s party instructed her to pursue López. I tracked Ortega down a few weeks ago, and we met for coffee in Bogotá. When I asked her about the criminal charges against López, she shook her head in dismay. “Without a doubt,” she said, “Leopoldo López is a political prisoner.”

Ortega told me it had been illegal to hold a civilian like López in a military prison. Over the course of three years, his conditions grew progressively worse. In the early stage, he was allowed to read and write, and a local university devised a program of study. He read Venezuelan poets, Ralph Waldo Emerson, the diary of Ho Chi Minh and a biography of Nguyen Van Thuan. He was consuming several volumes a week, until officials began to restrict what he could read. Eventually, they prohibited everything except the Bible. He read it from Genesis to Revelation. Then they took the Bible, too.

A migration center run by the Catholic Church in Cúcuta. Credit Sebastián Liste/NOOR, for The New York Times

Outside the refuge in Cúcuta, Colombia. Credit Sebastián Liste/NOOR, for The New York Times

He was moved to a new cell, then another. He spent months in solitary confinement in a room that was six feet by 10 feet. He would sit in silence trying to pray or meditate and summon any possible reason for gratitude: that he could feel himself breathing; that his wife and children were safe; that through the window he could hear the commotion of the outside world — a passing truck, a twisting wind, some emphatic bird.

Without his books, he reflected on those he had read. He remembered biographies of nonviolent leaders and the Birmingham letter from King, and he began to wonder if what they had in common wasn’t just a commitment to resistance but some deeper observation about the character of history. This came through most clearly in King. His goal was never just to provoke or confront. It was to locate the elusive fulcrum between conflict and mediation — to produce an onslaught of pressure that forced officials to react while preserving an almost irrational faith in their capacity for good will.

“I had an illumination moment,” López recalled. “One night, I couldn’t sleep, and I was tossing from one side of the bed to the other, thinking about the son-of-a-bitch director of the prison. I was very, very angry, and I woke up the next morning, and I said: ‘What am I doing? This guy is taking away my tranquillity, my sleep.’ ” He realized that the buildup of anger threatened to distort his thinking. He began trying to separate his outrage from his fury. He continued to defy the arbitrary rules of prison — composing and smuggling a stream of subversive messages to the outside — but when the guards would charge into his cell to look for contraband, shouting and tearing through his things, he searched for calm. He would stand back, lifting his hands in a posture of self-defense and say in the most measured tone he could muster that he would protect himself if necessary. In the hours between, the interminable stretches of solitude, he tried to be honest with himself about what anger had cost him. It wasn’t just a threat to his state of mind but to his politics, his movement and the way he conceived the future.

“In the past, I was in confrontation with different views,” he told me. “Now I understand that everybody is needed in order to reach a way out of this disaster.” He thought of books he had read on postwar Europe and the South African emergence from apartheid, and he realized that Venezuela would never find stability if it were cleaved into disparate sectors. It would be necessary to forge, like Mandela with F.W. de Klerk or King with Lyndon Johnson, some tentative confianza between the opposition and supporters of chavismo. “A lot of people in the opposition have resentment, and I understand that,” he told me. “But I think our responsibility is to move beyond the personal resentment. Four years in prison have given me the possibility of seeing things a different way, of putting rage in its perspective.”

A few nights ago, I was speaking with López a little before midnight. His family was asleep, and in the quiet hours he was bracing for the possibility that appearing in these pages could trigger his return to prison. This was something we had talked about many times. His eldest daughter was a toddler when he first went to prison and is now a little girl. His son had been less than a year old and was just now getting to know his father. At the end of January, López and Tintori had a second daughter, and it troubled him to think that years could pass before he saw any of his children again.

“It’s not easy,” he said quietly. “It’s not easy, but I have the responsibility to speak my mind. I’ve been in prison four years now because of speaking my mind, and if I self-censor, I’m beaten by the dictatorship.” López said he still believed that with the right leadership, Venezuela could rebound. He thought of postwar Japan and South Korea and Europe. He knew that stabilizing the bolívar could be accomplished by attaching its value to a foreign currency, and that under a new government, the private sector would return. He believed the country’s oil production would recover under good management, and he had been working for nearly a decade on a plan to convert the national oil company into a kind of Social Security trust, with investment shares assigned to the public for retirement, education and emergencies.

López with his children, Manuela (left) and Leopoldo, at home in January. Credit Diana López for The New York Times