Downward spiral: how Venezuela’s symbol of progress became political prisoners’ hell

by Emma Graham-Harrison in Caracas

The dizzying spiral structure in central Caracas was conceived in the 1950s as a monument to a nation’s confidence – but now its crumbling shell houses a notorious political prison. Is El Helicoide a metaphor for modern Venezuela?

Spiralling up a hill in the heart of Caracas is a playful, ambitious building that once embodied Venezuela’s dreams of modernity, power and influence, and was fêted by Salvador Dalí and Pablo Neruda.

Today, its crumbling concrete shell houses the headquarters of Venezuela’s intelligence services and the country’s most notorious political prison. It has become a symbol of national decay, bankrupt dreams and faltering democracy.

Slums on the surrounding slopes obscure the aging Buckminster Fuller dome that tops its elegant coils, but the building can still be seen from around the capital, and casts a long shadow of fear.

El Helicoide in front of San Agustin barrio. Photograph: Pietro Paolini/TerraProject

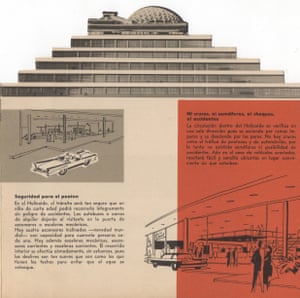

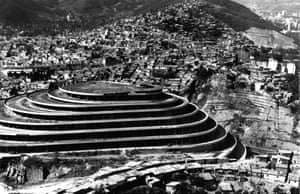

El Helicoide – as it was named in a nod to the geometry that inspired it – was conceived in the early 1950s as a shopping mall that would embody Venezuela’s wealth and confidence. Its curving lines are created by more than two miles of ramps in an interlocking helix, designed as a modern take on the high street.

The design included space for 300 boutiques, and parking spaces for each. There were also plans for a hotel and galleries. But the building was never finished, and the shops never opened. Instead, areas earmarked for the sale of luxury goods were turned first into shelters for the homeless, then prison cells, police headquarters and eventually even torture chambers, described by former inmates as “hell on earth”.

The planned interior. Photograph: Archivo Fotografía Urbana / Proyecto Helicoide

Several Venezuelan governments tried to remake El Helicoide as a museum or cultural centre, but all the efforts ended in failure. Its cells have never been as crowded as they are today, after months of street protests against the government of Nicolás Maduro that often turned violent. Support for his government has collapsed in the face of severe shortages of food and medicine, hyper-inflation and spiralling violence.

The president blames foreign sabotage for the country’s problems, even though Venezuela sits on the world’s largest oil reserves, and he has responded to the unrest by jailing and blacklisting opponents, convening a legislative super-assembly to sideline the opposition controlled parliament, and even openly flirting with “becoming a dictator to guarantee prices for the people”.

Celeste Olalquiaga, a cultural historian who grew up in Caracas, said: “El Helicoide is a metaphor for the whole modern period in Venezuela and what went wrong.” She has launched a project to document its extraordinary history and a book about the mall-turned jail.

The transformation from icon of Venezuela’s hopes to emblem of failure and repression was slow and complicated. It began with a coup, stretched over decades of dictatorship and democracy, through the rule of 14 presidents and several cycles of oil boom and bust. Someone looking for bad omens might have found one in the name of the hill where it’s built, Roca Tarpeya; the Tarpeian Rock was an execution ground in ancient Rome.

Construction on Roca Tarpeya, in about 1956. Photograph: Archivo Fotografía Urbana / Proyecto Helicoide

But after the project was unveiled in 1955, the first years of planning and construction were ones of steady progress and optimism. El Helicoide was so internationally celebrated that it was praised by Neruda, and Dali reportedly offered to help decorate the interior. But a 1958 coup that ousted the dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez from power swept away dreams for the mall along with much else.

El Helicoide was actually a private project, but Pérez Jiménez had become so famous for his grandiose construction plans that most Venezuelans assumed the dizzying mall was a state effort. As the country tried to move on from his brutal rule, everything associated with the ex-president was tainted – and that included El Helicoide. Without funding or support, the project collapsed and the near-finished building sat empty for years.

Meanwhile, Caracas was changing around it. Wealthy residents of the city moved east, and slums expanded south, until they all but engulfed El Helicoide.

The concrete shell, poured but never finished, became embroiled in legal action between the developers, the government and store owners who had made downpayments to purchase their space. Eventually in 1975 it came under government control.

El Helicoide abandoned, 1968. Photograph: Paolo Gasparini

The lead Venezuelan architect Jorge Romero Gutiérrez had sunk so much of his once considerable fortune into it that its failure all but bankrupted him. It also damaged his reputation and destroyed his spirit, said Alberto Sato, an architect and professor based in Chile.

Sato tracked down Romero – a personal hero of his – when he first came to Venezuela in the 1970s. He found a man bankrupted and broken by El Helicoide’s failure, who had largely abandoned architecture.

That was his country’s loss, says Sato. “He was a type of madman, incredibly visionary,” pointing out that El Helicoide is one of the few Caracas buildings distinctive enough to identify easily from the air. “I think that he was one of the most important architects of the 1950s in Venezuela, but his work wasn’t treated as it deserved.”

The building’s first permanent occupants did not move in until the mid-1970s, and could hardly have been further from original visions. When landslides swept away swathes of a nearby town, the government moved five hundred newly homeless families into temporary shelters on the ramps.

Conditions were extremely basic: neither electricity nor water supplies had ever been installed, and so the building offered little more than protection from the elements.

But that was attraction enough though for those who had lost everything, and before long, 2,000 families – 10,000 people – were crammed into the ramps, said Olalquiaga. Conditions were grim, and it soon became a centre for drug trafficking, prostitution and crime.

In 1982, the families were cleared out, and Sato worked on a project to turn El Helicoide into a cultural centre. Romero wanted little to do with the building that had ruined his reputation.

“He was too old, too tired, to have any real hope. I remember him saying ‘It’s cursed, you are not going to be able to do anything there,’ ” Sato said.

El Helicoide is ‘very anti-climactic, like a building equivalent of the Wizard of Oz’, says Celeste Olalquiaga, who was allowed inside on a visit. Photograph: Cristóbal Alvarado Minic/Getty

Romero turned out to be correct, at least as far as Sato’s project was concerned. After a change of government in 1984 and a foreign currency crisis, El Helicoide slipped back into disuse. Worried about squatters returning, the government moved the secret police in the next year.

Different iterations of the intelligence and security forces have been based in the building ever since 1985, with top floors serving as offices and the lower two as a jail. The cells are tiny and cramped, partly because of the deceptive nature of the building itself. It may look like a futuristic cruise liner, but most of its bulk comes from the hill that defines its basic form. The actual building is no more than the ramps spiralling up to the summit and back down.

“When you visit El Helicoide you realise that between the rock, which takes most of the centre of the site, and the ramps, there is very little useable space,” said Olalquiaga, who was allowed inside on a visit in 2015.

“It’s very anti-climactic, like a building equivalent of the Wizard of Oz. From outside you see a huge thing, but from inside you see that it’s kind of small,” she said. “I call it a living ruin as it’s semi-abandoned.”

Even the indefatigable populist president Hugo Chávez was defeated by El Helicoide, which he described as both “cursed” and “very important”. At one point he ordered the intelligence services to leave and promised to turn the ramps into a social centre, but the officers and their prisoners never did depart and the grand project never materialised.

A protester takes aim at riot police during anti-government protests in Caracas, May 2017. Photograph: Cristian Hernandez/EPA

There are no records of who was jailed in the early years. The first man known to have been held for his views was an astrologer, José Bernardo Gómez. He was arrested the 1990s for forecasting the impending death of the country’s then president, Rafael Caldera (who was then in his late 70s) – a crime that seems almost as strange as the building where he was held.

“I was held prisoner at El Helicoide 21 years ago,” said Gómez, who is still reading the stars. “In those years the government (the president) reacted in this way because I had shared my astrological readings at a private event for businessmen.” (On his release in 1996, El Nacional newspaper quoted Gómez defiantly clinging to his reasons for seeing mortality in the alignment of Pluto, Uranus, Mars and the comet Chiron, though Caldera lived on until 2009.)

Since then, hundreds of others have followed in Gómez’s footsteps, including both regular prisoners and those locked up for their political views.

Rosmit Mantilla, an LGBT activist and opposition politician, said: “The Helicoide is the centre of torture in Venezuela. It’s a hell on earth.” Desginated a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty, he spent two and a half years imprisoned in the building.

He endured psychological torment and physical abuse, but believes he was spared the most extreme torture thanks to an international campaign for his release. He decided to compile a record of what he saw and heard from fellow prisoners, and has worked to raise awareness since his own release in November last year.

He describes a routine of overcrowding and malnutrition, psychological pressure and sparse rations as universal. Some endured worse treatment.